[[H I S T O R Y]] * [Author’s note: This will be a very light blogging week, as I’m traveling to San Francisco to help commemorate the 100th anniversary of that California city’s great earthquake and fire--one of the worst disasters in American history. Having written much about the city’s past, most notably in my 1995 book, San Francisco, You’re History!, I wouldn’t think to miss this opportunity to relive the 1906 catastrophe that destroyed the town’s first incarnation, and birthed a second-century San Francisco that, while subordinate to Los Angeles in size, nonetheless remains one of the greatest metropolises in the world. I intend to be among those hardy souls who, at 4:30 a.m. on Tuesday, April 18, will be crowded around the landmark Lotta’s Fountain on Market Street for a ceremony marking the exact time when, a century before, San Francisco, a city that had sprung up from nothing in response to the California Gold Rush, was reduced to almost as little by Mother Nature. In the meantime, I’m posting this remembrance of the earthquake and subsequent conflagration, combining material from a couple of chapters in San Francisco, You’re History! Even if you can’t join me on Market Street in the cold predawn of April 18, I hope you’ll come away from reading this with a better understanding of the disaster born there 100 years ago.]

* * *

“There was a deep rumble, deep and terrible, and then I could see it actually coming up Washington Street. The whole street was undulating. It was as if the waves of the ocean were coming towards me, billowing as they came.”The speaker, a police sergeant named Jesse Cook, who was on duty in San Francisco’s produce district during the early morning hours of Wednesday, April 18, 1906, remembered later that he didn’t even have time to react before the city’s most violent earthquake smacked him to the ground.

It began just after 5 a.m., on what San Francisco Chronicle editor Ernest Simpson later recalled was “as fair a morning as ever shown upon the world.” Suddenly, the earth ruptured along the 296-mile San Andreas Fault with a force equal to 15 million tons of TNT, the quake’s epicenter located a mile offshore from Mussel Rock, southwest of the Golden Gate and adjacent to what’s now the suburban community of Daly City. Forests of mighty redwoods were toppled like so many toothpicks. Ships 150 miles out in the Pacific were jolted, their captains convinced that they had somehow struck a reef or a wreck twisting up from the deep sea floor. Fort Bragg, a blue-collar hamlet on the Mendocino Coast, jiggled and collapsed. The 110-foot-high Point Arena lighthouse, 90 miles north of San Francisco, swayed like a hula dancer before it too disintegrated in a hazardous hail of glass shards and broken masonry. At Point Reyes Station, also north of the city, the southbound morning train was tossed into the air as its track buckled with the release of subterranean pressure. Boats docked at Bolinas were snapped clear of their moorings, and the town’s wharf slipped underwater. South of San Francisco, 14 buildings at Stanford University in Palo Alto were demolished, along with the main quadrangle. Twenty-one men, women, and children perished in San Jose. A telephone operator in San Luis Obispo heard a scream on the other end of the line, and then her scratchy connection with Salinas went dead.

At just after 5:12 a.m., 20 minutes before dawn, the shock pummeled San Francisco. There were actually two tremors, lasting less than a minute, with an eerie and falsely reassuring few seconds of calm in between. The second shock was the bigger of the pair, being felt as far north as Oregon and all the way south to Los Angeles. The Richter magnitude scale hadn’t yet been developed in 1906, but estimates since then have rated this seismic convulsion at 7.8 magnitude (down from an original estimate of 8.3), on a scale of 1 to 10. The great quake’s effects were picked up by seismographs even in far off Birmingham, England, and Tokyo, Japan.

Most of the force was concentrated north and south of San Francisco. The quake was powerful enough, though, to send earth waves, two to three feet high, roaring through the ground, threatening the foundations of even the strongest buildings in the city and bringing lesser edifices down with ear-splitting crashes.

And the quake was only the beginning of a three-day disaster that would bring an end to San Francisco as it was.

* * *

One of the first buildings to go was City Hall, finished only six years before, after three decades of slow work. The shaking caused almost the entire façade of the building to peel away, until all that remained was the metalwork beneath. The once-elegant dome looked like nothing so much as a bird cage. Streetcar tracks reared up from their bolts and bent around like angry snakes. Long jagged tears opened the concrete middles of streets. Water gushed from broken lines. Gas spit up from rents in the sidewalk. Streets were quickly choked with dust from falling brickwork. At the Ferry Building, anchoring the west end of Market Street, the tower clock stopped, and the tower itself weaved drunkenly and threatened to give way. Structures erected on landfill that covered Yerba Buena Cove sagged into the ground, twisted unnaturally, their wood siding springing free with loud whines. At wharves, scaffolding collapsed, chopping boats in half. Hundreds of cemetery headstones tumbled over, all falling toward the east. What remained of gaslights fighting the darkness went out immediately. Horses, spooked by the commotion, by the sparks thrown off from severed power lines, by people screaming all around them, broke their tethers and stampeded through downtown, joining platoons of rats already running for their pitiful lives. Joining the ruckus was a herd of longhorn cattle, which had recently been unloaded into the city and were being driven by Mexican vaqueros to stockyards in the south of town. The drivers abandoned their charges the moment the shocks commenced, and the steers went charging up Mission Street.

Streetcar tracks reared up from their bolts and bent around like angry snakes. Long jagged tears opened the concrete middles of streets. Water gushed from broken lines. Gas spit up from rents in the sidewalk. Streets were quickly choked with dust from falling brickwork. At the Ferry Building, anchoring the west end of Market Street, the tower clock stopped, and the tower itself weaved drunkenly and threatened to give way. Structures erected on landfill that covered Yerba Buena Cove sagged into the ground, twisted unnaturally, their wood siding springing free with loud whines. At wharves, scaffolding collapsed, chopping boats in half. Hundreds of cemetery headstones tumbled over, all falling toward the east. What remained of gaslights fighting the darkness went out immediately. Horses, spooked by the commotion, by the sparks thrown off from severed power lines, by people screaming all around them, broke their tethers and stampeded through downtown, joining platoons of rats already running for their pitiful lives. Joining the ruckus was a herd of longhorn cattle, which had recently been unloaded into the city and were being driven by Mexican vaqueros to stockyards in the south of town. The drivers abandoned their charges the moment the shocks commenced, and the steers went charging up Mission Street.Like some complex nightmare or surreal stage drama, the quake has left us with thousands of such bizarre scenes, each one seeming to exist separately, although we know that they are tied together by a natural phenomenon.

In The Damndest Finest Ruins (1959), one of the most readable accounts of the April 18 catastrophe, author Monica Sutherland tells of a flophouse lodger who woke in his dirty bed, still partially intoxicated from the night before, to find the furniture around him bouncing up and down on the floor. Looking up at the ceiling in his bleary-eyed delirium, the man saw a crack open up and a child’s bare foot come poking through, “like some ghastly hanging lamp.” As the building swayed, that crack closed again, “and the tiny foot, snapped off at the ankle, fell down soft and bleeding onto his bed.” The terrified transient leapt up and hurled himself from the flophouse window. That act saved his life, for within minutes the building he’d left was rubble.

Above a fire station on Bush Street, Dennis T. Sullivan, the city’s fire chief (who’d argued for years that San Francisco was a tinderbox awaiting a match), was jolted from his slumber by the belligerent rocking and the crash of chimneys from nearby edifices. Getting up quickly, he rushed toward the back bedroom where his wife had been staying. But before he could reach her, a brick chimney from the adjoining California Hotel punched through the firehouse roof, taking out part of Mrs. Sullivan’s bedroom floor. Unable to manage a clear view through the resulting dust cloud, the chief stepped forward to see if his wife was all right ... and fell three stories down through the hole that had been opened by the chimney. He landed on a fire wagon, his skull, arms, and legs badly fractured. Although his spouse survived the calamity, little scathed, Sullivan himself died in a hospital three days later, without enjoying even a moment’s role in combating the blaze that might have made him famous.

* * *

Meanwhile, at the elegant Palace Hotel on Market Street--the largest hotel in the country at that time, seven stories tall and ribboned on its face with parallel banks of bay windows--renowned Italian tenor Enrico Caruso, in town for a week with the Metropolitan Opera Company to sing the role of Don José in Carmen, was bawling his head off. Caruso, not inclined to adapt easily to new surroundings, hadn’t wanted to visit the Bay Area in the first place. When the second temblor of April 18 stilled and the cacophony subsided into an equally frightening hush, Caruso was convinced that his life was over. Worse, he was sure that he’d lost his voice. When Caruso’s conductor, Alfred Hertz, rushed into the star’s bedroom, he found his charge despondent amidst piles of boots, silk shirts, and broken chandeliers. Hertz tried to calm Caruso, but with only limited success. Finally, he told the tenor to come to the open window and see for himself that the quake--or at least its initial rampage (there would be 135 aftershocks on April 18, and 22 on April 19)--was spent.“The street presented an amazing series of grotesque sights,” Hertz later recorded. “Most people had fled from their rooms without stopping to dress, many of them a little less than naked. But excitement was running so high that nobody noticed or cared.” Above this mêlée, Hertz instructed Caruso to sing. To reassure himself that he could. And Caruso did just that. At the top of his lungs. At the top of his form. One can only imagine the confusion engendered by this tableau. The Queen City of the Pacific Coast was a shambles, women were running down wide Market Street with babies squeezed against their breasts, men were hobbling along with prized belongings, smoke was rising from the Chinese quarters of town ... and the world’s greatest living tenor was bellowing lines from Carmen out a fifth-floor window at the Palace. People below stood transfixed by the absurdity of it all.

They didn’t remain still for long, for no sooner had the quake ended than the fires began. With all the crossed power lines, upended coal and wood stoves, broken vials of ignitable chemicals, and flammable-gas leaks, combined with the dry debris so recently exposed, the city’s combustibility was at an all-time high. Yet not a single fire bell could be heard clanging. Wrecked along with so much else that morning was the fire department’s central alarm system, housed in Chinatown.

While the tremors caused havoc in the city, it was fire that really sealed San Francisco’s fate. Despite several city-destroying blazes during the 19th century, California’s most prominent town was still built primarily of wood. Chief Sullivan’s forces did their best, rushing into the heart of the disaster, braving incinerations so hot that the firemen’s hair was singed as they moved in with hoses. But it was all for naught. In most cases, hoses attached to hydrants brought forth little more than a trickle. The 30-inch mains leading to San Francisco’s two primary reservoirs in San Mateo County were broken.

Water pipes within the city were also split and non-functioning. Water leaked everywhere, and little was left to throw onto the raging flames. Huge cisterns that had been located decades before under major intersections, for use in just such emergencies, ran dry in no time flat. Sewer water was pulled up by the gallon and heaved against the incendiary demons, but it made little difference. Firemen, even the bravest of the lot, were forced into hasty retreat. Half an hour after the earth stopped shimmying, the city was engulfed in great, mephitic clouds of smoke five miles high that convinced onlookers in adjacent Oakland and Berkeley (where the earthquake had barely been felt) that San Francisco would soon be utterly destroyed.

Thousands of refugees fled before the scalding onslaught, carrying their possessions. Mobs rushed to the ferry docks, begging for passage to the East Bay. Some had barely escaped the fires, and their scorched bowlers and flame-fingered dresses showed just how close they’d come to being painful statistics. Through the middle of this panic drove automobiles retrieving the earthquake dead, their bloody, featureless faces staring out at people still hoping to weather the calamity.

Caruso had no intention of waiting out the city’s consuming disaster. So, after fleeing the Palace Hotel, he and two members of his company embarked for the Ferry Building, hoping to secure passage across San Francisco Bay and then a train heading east. But when they arrived at the terminal, according to Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts, in The San Francisco Earthquake (1971), the group was told to wait in line along with everyone else. This was too much for the spoiled Italian. “I am Enrico Caruso,” he announced. “The singer.” When the railroad man appeared unimpressed, Caruso drew out a signed portrait of Theodore Roosevelt that he had carried with him from the Palace and shouted, “I am a friend of President Roosevelt. See. He gave me this!” And as the bewildered official studied the photo of the toothsome chief executive, Caruso added, “He is expecting me in Washington!” Another railroad man was called over, and the pair consulted for a few minutes. Then the new official said to the beefy tenor, “You Enrico Caruso? Then sing.” “Sing! I want to leave here!” retorted the tenor. “Sure,” the railroader remarked skeptically. “But you sing first.” And so the vocalist who had never wanted to come to San Francisco in the first place was forced to belt out a few more lines from Carmen, just to earn his exit from town. Amazingly, it worked. Within a few minutes, Caruso and his party were on a ferry bound for Oakland.

Not everybody was so unnerved by the disaster building in San Francisco. On the Barbary Coast, the city’s infamous center of salaciousness, men and women whooped it up, taking whatever liberties they were allowed in the belief that all was lost and they might as well enjoy their last hours of life. Elsewhere in the city, looting of saloons and liquor stores was commonplace. The threat from mob violence was so acute in North Beach, the city’s Italian province, that even the firemen working there took to packing guns. Musician-turned-mayor Eugene Schmitz finally proclaimed that law-enforcement personnel “have been authorized to KILL any and all persons found engaged in looting or in the commission of other crimes.”

* * *

Watching the city burn from high up on Washington Street, Brigadier General Frederick Funston decided it was time for him to do something. Short and slight, Funston was nonetheless known to charge through point-blank gunfire in pursuit of a strategic goal. After proving his mettle during the Spanish-American War and in the Philippines, the red-headed Funston had arrived in 1901 at San Francisco’s Presidio, the city’s armed forces preserve, as second-in-command of California’s military department. It was not an easy posting for him. He didn’t trust Mayor Schmitz’s corrupt administration, for which he was acting as a liaison to the army, and he missed the thrill of battle. But now, with San Francisco staggering on the edge of ruin, Funston saw a chance to exercise his command skills.Not so surprisingly, the brigadier general didn’t consult with Schmitz--a breach of protocol that would be criticized in the weeks to come. Nor did he have the approval of his superiors in Washington, D.C., before he took action. Yet he ordered his troops to march right away upon the city and do whatever they could to restore order, end the looting, organize first-aid services, and help extinguish the flames. Then “Fearless Freddie,” as he’d later be dubbed, telegraphed appeals to the army

installations at Alcatraz Island, in Marin County, and as far away as Portland, Oregon, asking for additional troops to save San Francisco. By mid-morning, he had placed the City by the Bay under martial control.

installations at Alcatraz Island, in Marin County, and as far away as Portland, Oregon, asking for additional troops to save San Francisco. By mid-morning, he had placed the City by the Bay under martial control.While all of this was going on, the town’s much-scattered, separate fires coalesced into three major ones--south of Market Street, north of Market near the waterfront, and in Hayes Valley, to the west of City Hall. This last blaze, the so-called Ham and Eggs Fire, was apparently started by a woman blithely cooking breakfast in an earthquake-damaged chimney. Her house presently caught ablaze, and the fire spread.

Small successes were being logged against the conflagration. The waterfront survived because fireboats rushed in to spray down flammable warehouses and sheds, and the Jackson Square area was saved because a naval force led by Lieutenant Frederick Newton stretched a mile-long hose from Meiggs’ Wharf (which began near Francisco and Mason streets, well inland from today’s Fisherman’s Wharf) up and over the top of Telegraph Hill, and used salt water to douse the flames. On the disaster’s second day, Italians struggling to save houses around Telegraph Hill broke open casks of red wine--some 500 gallons of it--and sloshed it over roofs, floors, walls. Tongues of fire licked at the wine-drenched edifices and backed away in pursuit of drier feed.

But the efforts of firemen and Funston’s forces to create firebreaks by dynamiting buildings in the holocaust’s path--a practice that had been popular in the 19th century--were a failure more often than not. First, imprecise loading of explosives meant that some shanties, rather than imploding, were blown to smithereens, sending more tinder into the maw of approaching flames or peppering already burning debris onto previously untouched structures. Then, the firebreaks were neither wide enough nor far enough ahead of the calamity to be truly effective. Mayor Schmitz, chary of political fallout from a wholesale demolition of private property, had insisted that buildings be dynamited only if they were in immediate danger of ignition. This caution proved tactically reprehensible.

For most of the day, it seemed that the Palace Hotel--the grandest of accommodations in a city that even back then was rife with lodging houses, covering 2.5 acres and containing 800 rooms--would be all right. Raised by local banker William C. Ralston and opened in 1875, the hotel had been constructed to withstand almost anything. To protect against earthquake damage, the outer walls were two feet thick, and double strips of iron reinforced them at four-foot intervals. And tucked into the sub-basement was a reservoir able to hold 630,000 gallons of water. Fed by a series of artesian wells, the Palace’s reservoir guaranteed that its distinguished, high-paying guests would have water even if the city’s ample supplies went dry. It was also meant to ensure a water supply in the event of a fire at the hotel. A trio of pumps in the basement kept water pressure high, and there were 35 outlets around the building where hoses could be attached. Seven tanks on the roof contained an additional 130,000 gallons of water. Ralston even installed rudimentary electric fire detectors in every room and scheduled hallway patrols at 30-minute intervals day and night. The supposition was that, should the rest of San Francisco burn to a crisp, the Palace would remain standing.

As flames licked their way up from the neighborhoods south of Market on April 18, 1906, spectators outside the Palace were heartened to see jets of water showering its two-acre roof. While firemen in other parts of the city found hydrants inoperable, hose-wielding Palace employees fended off the hot ashes that rained down from a black sky. But while Ralston and his engineers had planned well against sudden conflagrations, they hadn’t figured on such a prolonged battle. By early afternoon of that terrible day, the reservoir beneath the hotel and its rooftop tanks had been bled dry, while flames rose on all sides of the Palace, consuming the three-story, multi-domed Grand Hotel on the east and the new Monadnock Building to the west. By half past three o’clock, the now abandoned Palace “presented the appearance of being afire in every part ...,” recalled San Francisco Chronicle managing editor John P. Young. “The spectacle was one calculated to inspire awe despite the fact that all around it were structures which had already succumbed to the destroyer.” As fire ravished this previously impervious “symbol of San Francisco’s coming of age” (to quote Oscar Lewis and Carroll D. Hall in Bonanza Inn [1939]), crowds cheered to see a single American flag still fluttering atop a pole on the Palace’s Market Street side. Not until that banner disappeared in the smoke and angry candescence of the fire was the San Francisco That Had Been finally deemed dead.

By the end of that first day, the city was in the process of being consumed by one humongous blaze that kept the night sky lighted. Although many people remained upbeat about their chances of survival, others interpreted this as a signal fire marking the end of the world. Rumors spread of other disasters: Manhattan Island had sunk already, it was said; Chicago was now at the bottom of Lake Michigan; the entire West Coast was aflame. Just before the San Francisco earthquake, news had come that Italy’s Mount Vesuvius was, in fact, erupting. All of this convinced the city’s more fanatical residents that divine retribution, rather than natural forces, was to blame for their hardships. “This is the lord’s work!” they whispered.

* * *

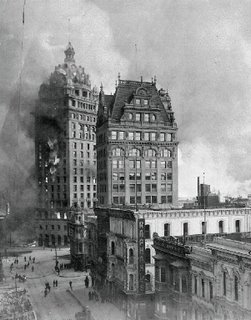

The fire continued for 74 hours, until Saturday morning, April 21, when it finally burned itself out. Rain began to fall not long after that--a little late, but nonetheless welcome. Late, as well, was official authorization from the nation’s capital permitting Brigadier General Funston to take command of the situation as he had already done: It arrived by telegram on April 27.All in all, the fire razed more than 28,000 buildings--between $500 million and $1 billion in property--over an area of 4.7 square miles, between Larkin Street on the west and 20th Street on the south. Temperatures in the thick of the disaster had climbed as high as 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. “An enumeration of the buildings destroyed would be a directory of San Francisco,” novelist Jack London lamented in Collier’s magazine soon after the terror had passed. “An enumeration of the buildings undestroyed would be a line and several addresses.” A few landmarks, such as Telegraph Hill, Jackson Square, and the old U.S. Mint, at Fifth and Mission streets, survived with minimum damage. But many of the places that had defined the character of San Francisco were horribly defaced or destroyed altogether. The elegant Call Building was gutted, as was the Examiner Building, both headquarters for newspapers on Market Street. At the height of the catastrophe, Nob Hill--with all its extravagant alcazars, the retreats of moguls who’d made their millions on gold and railroading and the sweat of their less fortunate fellows--looked like a lit match head. Even a team of scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey, sent into the city after Mother Nature had turned it into a devil’s playground, couldn’t contain their astonishment. “The whole civilized world stood aghast,” the team recorded, “at the appalling destruction.”

About 225,000 San Franciscans--more than half of the city’s entire population--were left homeless by this Edwardian disaster. Many of them fled to Oakland or retreated to Golden Gate Park and the Presidio, where they set up temporary tent cities reminiscent of those that had dotted the town during its Gold Rush frenzy half a century before. Estimates of the numbers killed in the earthquake and fire have varied from 478 (a deliberately low-ball count in the immediate aftermath of the catastrophe) to 6,000, though something just upwards of 3,000 is more likely. (Even that is more than 10 times as many people as perished in the country’s second-worst fire, at Chicago in 1871.) Mass funerals were held all over town. Dead animals were left to decompose, adding the stink of rotting flesh to the pervasive odor of wet, burned wood.

Everywhere, there was a sense that the city would never be the same again. Yet expectation was rife in the air. “The great calamity ... left no one with the impression that it amounted to an irrevocable loss ...,” English writer H.G. Wells explained some years later in The Future in America: A Search After Realities. “Nowhere is there any doubt but that San Francisco will rise again, bigger, better and after the very briefest of intervals.”

And so it did.

READ MORE: Photographs: San Francisco, the Day Before the Great Quake; “The Great Quake: 1906-2006” (San Francisco Chronicle); “100 Years After the San Francisco Quake” (National Public Radio); The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire (The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco); Timeline of the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire (The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco); 1906 Earthquake Image Gallery (California Historical Society); The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire (Bancroft Library, University of California-Berkeley); Videos of the Earthquake Aftermath (Internet Archive); “Before and After the Great Earthquake and Fire: Early Films of San Francisco, 1897-1916” (Library of Congress); “San Francisco in Ruins: The 1906 Aerial Photographs”; “A Letter from the Quake Zone” (The Seattle Times); 1906 Earthquake Centennial Alliance.

1 comment:

good site

manoj kumar

Post a Comment