In his July 24 column, The New York Times’ Frank Rich speculates that the reason Bush passed up nominating U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales to the Supreme Court wasn’t because he was “scared off by Gonzales critics on the right (who find him soft on abortion) or left (who find him soft on the Geneva Conventions).” Instead, it was because of Gonzales’ proximity to this scandal centered on the “outing” of CIA agent Valerie Plame to the media in 2003. As then-White House counsel, Rich writes,

[Gonzales] was the one first notified that the Justice Department, at the request of the C.I.A., had opened an investigation into the outing of Joseph Wilson’s wife. That notification came at 8:30 p.m. on Sept. 29, 2003, but it took Mr. Gonzales 12 more hours to inform the White House staff that it must “preserve all materials” relevant to the investigation. This 12-hour delay, he has said, was sanctioned by the Justice Department, but since the department was then run by John Ashcroft, a Bush loyalist who refused to recuse himself from the Plame case, inquiring Senate Democrats would examine this 12-hour delay as closely as an 18½-minute tape gap. “Every good prosecutor knows that any delay could give a culprit time to destroy the evidence,” said Senator Charles Schumer, correctly, back when the missing 12 hours was first revealed almost two years ago. A new Gonzales confirmation process now would have quickly devolved into a neo-Watergate hearing. Mr. Gonzales was in the thick of the Plame investigation, all told, for 16 months.Responding to some of Rich’s allegations on the CBS Sunday morning program Face the Nation, Gonzales insisted there was “nothing improper about waiting 12 hours to ‘preserve all

materials’ after being informed by the Justice Department ... that it was launching an investigation into the disclosure of Valerie Plame’s status as a CIA agent.”

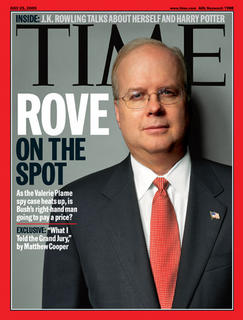

materials’ after being informed by the Justice Department ... that it was launching an investigation into the disclosure of Valerie Plame’s status as a CIA agent.”Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Times reports that Patrick J. Fitzgerald, the special prosecutor in the CIA leak investigation “has shifted his focus from determining whether White House officials violated a law against exposing undercover agents to determining whether evidence exists to bring perjury or obstruction of justice charges” against deputy chief of staff Karl Rove and vice-presidential chief of staff Lewis “Scooter” Libby. It seems discrepancies may exist between what Rove and Libby told federal agents and a grand jury about their involvement in the leaking of CIA agent Valerie Plame’s identity to the media, and what reporters have testified regarding their contacts with both officials. As the paper explains, “Disclosing the identity of a CIA undercover agent is a crime under some circumstances, but legal experts have said that elements of the law make it difficult to prove a violation. Prosecutors could have an easier time winning a conviction under another law that makes it a crime for officials with security clearances to disseminate certain information. According to that statute, it could be a crime to have confirmed that Plame was a CIA agent if she was operating undercover.”

Finally, although the media focus right now is on what Rove and Libby (and perhaps others in the exceedingly partisan Bush White House) did to “out” Plame in retaliation against her husband, former ambassador Joseph Wilson, who had accused the administration of distorting its prewar intelligence on Iraq, the broader question--“How much did the president know, and when did he know it?”--remains the elephant in the room. So far, Bush and White House spokesman Scott McClellan have ducked questions about the leak, citing the ongoing criminal probe. But, notes The New York Times, “Democrats increasingly see an opportunity to raise questions about Mr. Bush’s credibility, and to reopen a debate about whether the White House leveled with the nation about the urgency of going to war with Iraq. And even some Republicans say Mr. Bush cannot assume that he will escape from the investigation politically unscathed. ‘Until all the facts come out, no one is really going to know who the fickle finger of fate points at,’ said Tony Fabrizio, a Republican pollster.”

ADDENDUM: Thanks to the trivia hound who wrote in to remind me that the term “fickle finger of fate” came to national prominence on the TV comedy-variety series Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, which was popular during the Nixon administration. “Certainly,” this reader quips, “Fabrizio didn’t mean to suggest a connection between Richard Nixon’s Watergate woes and Bush’s Plamegate disgrace, did he?” Veddy eeenteresting!

No comments:

Post a Comment