My own books collecting doesn’t seem nearly so concerning as Murdoch’s, and perhaps Macintyre’s. Thanks to a voracious reading appetite, as well as various stints as a critic and book review editor, I have shelves all over my house weighted down with fiction and non-fiction of every sort. I even had to create a library-office in my previously unfinished basement, just to accommodate the superfluity of words and brilliant sentences and inspired texts in need of my cherishing. As Macintyre explains, “Books have a self-hoarding, expanding quality. Unlike almost everything else in our society, they are enormously difficult to throw away. Once we have read them, they become part of our souls, a physical spur to memory. If we have not read them, they are even harder to jettison; they stand there on the shelf accusingly, worlds undiscovered.”

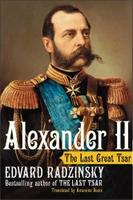

Occasionally, my wife will wonder at the sheer volume of volumes decorating our abode, stacked in every corner, peering out from every box and basket. “They’re good for research,” I say, defensively, positioning myself in front of whichever bookcase she is eyeing with suspicion. And that can certainly be true. But how, then, to explain my retention of Jonathan Safron Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close, a novel I shall likely never pick up again, and which I wasn’t all that keen on in the first place? Or the 1982 Omni Future Almanac, a collection of scientific tidbits and futurist folly (edited by Robert Weil) that is now well out of date? Or Donald R. Morris’ The Washing of the Spears: The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation, a work I procured long ago in trade for some other books, but which after all these years is still unable to climb anywhere near the top of my to-be-read pile? Novelist Anthony Burgess once said that “The possession of a book becomes a substitute for reading it,” and he has a point: Once we own a particular volume, we know that we can digest it at our leisure, anytime we want, though that anytime may never come to pass. There’s another dynamic at work too, however, which is that the amassing and display of books confers upon its owner a certain intellectual profundity. I’m always suspicious when I go into homes and see no books lined up neatly on shelves, or even piled on nightstands. Do these people not read? I wonder. Are they so shallow or self-satisfied that they think themselves above the expansion of mind and experience that books provide? There’s a part of me that wants to be known for the company of books I keep. And I’m not alone in that. In fact, it’s why people gravitate toward bestsellers like Dan Brown’s The DaVinci Code or Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian: to look like part of the “in crowd.” And why George W. Bush took Edvard Radzinsky’s not-yet-published biography, Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar, along with him on holiday this month--not necessarily to read, but to look like somebody who could read and appreciate Radzinsky’s wonderfully composed Russian history. (This is much in contrast to Bush’s predecessor, Bill Clinton, who was famous for packing along myriad books whenever he left D.C. on vacation, and for later discussing them at length.)

Occasionally, my wife will wonder at the sheer volume of volumes decorating our abode, stacked in every corner, peering out from every box and basket. “They’re good for research,” I say, defensively, positioning myself in front of whichever bookcase she is eyeing with suspicion. And that can certainly be true. But how, then, to explain my retention of Jonathan Safron Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close, a novel I shall likely never pick up again, and which I wasn’t all that keen on in the first place? Or the 1982 Omni Future Almanac, a collection of scientific tidbits and futurist folly (edited by Robert Weil) that is now well out of date? Or Donald R. Morris’ The Washing of the Spears: The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation, a work I procured long ago in trade for some other books, but which after all these years is still unable to climb anywhere near the top of my to-be-read pile? Novelist Anthony Burgess once said that “The possession of a book becomes a substitute for reading it,” and he has a point: Once we own a particular volume, we know that we can digest it at our leisure, anytime we want, though that anytime may never come to pass. There’s another dynamic at work too, however, which is that the amassing and display of books confers upon its owner a certain intellectual profundity. I’m always suspicious when I go into homes and see no books lined up neatly on shelves, or even piled on nightstands. Do these people not read? I wonder. Are they so shallow or self-satisfied that they think themselves above the expansion of mind and experience that books provide? There’s a part of me that wants to be known for the company of books I keep. And I’m not alone in that. In fact, it’s why people gravitate toward bestsellers like Dan Brown’s The DaVinci Code or Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian: to look like part of the “in crowd.” And why George W. Bush took Edvard Radzinsky’s not-yet-published biography, Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar, along with him on holiday this month--not necessarily to read, but to look like somebody who could read and appreciate Radzinsky’s wonderfully composed Russian history. (This is much in contrast to Bush’s predecessor, Bill Clinton, who was famous for packing along myriad books whenever he left D.C. on vacation, and for later discussing them at length.)Books supply us with entertainment, knowledge, and escape. As Macintyre observes, they also keep us connected with our histories; in browsing my shelves, memories flood back to me of youthful summers and long-ago journeys and trying times associated with the works arranged ever so neatly there. I can lay my hands on tomes that my late parents, and my later grandparents and great-grandparents, once enjoyed. I can find inscriptions left behind by past acquaintances and passing lovers. I can still hear the friend who gave me my copy of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove: “I know you’ll enjoy this one as much as I did.” Handling Gore Vidal’s Lincoln again, I am reminded of the days-long stretch I spent one autumn, reading that splendid historical novel during a travel-writing assignment to southeastern Alaska that was interrupted by the most torrential and incessant rainstorm I’d ever witnessed. In the absence of these books, these longstanding but generally unobtrusive compatriots, such recollections might not fully disappear, but they would undoubtedly be less frequently accessed.

So, while Macintyre advises periodically trimming back one’s book collection (if only to prevent mortal hazards, should some unexpected disaster cause leather bindings and dry pages of typescript to tumble from the walls), I choose instead to simply pack my volumes in a bit tighter. Like a lifetime’s worth of friends, standing shoulder to shoulder in a room, with everyone having something interesting to say.

No comments:

Post a Comment