[[M U S I C]] * One never really knows, growing up, just how significant individual events will turn out to be. As a child of 6, I remember being sent home from school on the afternoon of November, 22, 1963, after learning that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas, Texas. I didn’t know then how deeply that date would sear itself into the American consciousness, all I knew was that I came home to find my mother crying in front of the TV set. Two days later, I was again in front of the tube, but this time alone, as I watched Kennedy’s killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, being moved from Dallas police headquarters--only to be shot to death by a nightclub owner named Jack Ruby. I recall sitting in front of the flickering screen, my young mind unable to determine whether what I was seeing was fact or fiction.

[[M U S I C]] * One never really knows, growing up, just how significant individual events will turn out to be. As a child of 6, I remember being sent home from school on the afternoon of November, 22, 1963, after learning that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas, Texas. I didn’t know then how deeply that date would sear itself into the American consciousness, all I knew was that I came home to find my mother crying in front of the TV set. Two days later, I was again in front of the tube, but this time alone, as I watched Kennedy’s killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, being moved from Dallas police headquarters--only to be shot to death by a nightclub owner named Jack Ruby. I recall sitting in front of the flickering screen, my young mind unable to determine whether what I was seeing was fact or fiction.Funny how so many of the momentous memories from my boyhood seem to revolve around TV images. And here’s another one: On Sunday evening, February 9, 1964, I was visiting my grandparents in Portland, Oregon. My Canadian-born grandfather was a loyal watcher of The Ed Sullivan Show, so naturally the set was on when Sullivan announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Beatles!” Little did I know that 73 million other people were watching that performance, too--some 45 percent of the U.S. population. What I remember is that I couldn’t even hear the opening of “All My Loving,” thanks to the screaming and carrying-on of girls amassed in the CBS auditorium that night.

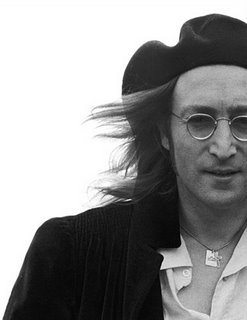

So many years ago. So much has happened since, for good and ill. Yet I am reminded of that opening night of America’s “Beatlemania” phenomenon as I contemplate another historic date: December 8, 1980--25 years ago today. It was late that evening when John Lennon--singer, guitarist, and the man who (with Paul McCartney) gave the Beatles their distinctive sound--returned to his home in New York’s City Dakota building, only to be shot four times by a demented, born-again Christian fan named Mark David Chapman. Despite his injuries, the singer managed to stagger up his building’s steps and collapsed before the concierge booth, saying, “I’m shot, I’m shot.” By the time police arrived on the scene, Chapman--disarmed--was sitting quietly outside the Dakota, reading J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Lennon was rushed to Roosevelt Hospital, but there was nothing that could be done to save him. He died around 11:15 p.m.

Lennon was only 40 years old.

As crowds gather today at Central Park’s Strawberry Fields, opposite the Dakota, to mark this 25th anniversary of Lennon’s demise with flowers, songs, and stories shared of appreciating both this one man and the Beatles as a group, it’s worth all of us stopping for just a moment, just a fraction of this busy workday, to recall what gifts that poetic, eccentric, and oh-so-human British rocker gave to the world. As Mikal Gilmore writes in his anniversary essay for Rolling Stone:

Nobody ever pushed the possibilities of rock & roll like John Lennon, and nobody in the music’s history has really mattered as much. This isn’t to say that Lennon was the primary reason for the greatness of the Beatles, though the Beatles are, of course, unimaginable without him. Nor is it to say that after he left that group he necessarily made better albums than the other former Beatles--though he made more interesting and consequential ones, and he took greater risks. And it isn’t to say that he led a life of uprightness or sanctity, because--and this is the important one--he didn’t. With songs like “Give Peace a Chance” and “Imagine,” Lennon idealized optimism and compassion, but he realized those ideals in himself only fleetingly. He had a notorious, biting temper, he wasn’t always fair to the people who loved and trusted him, and he sometimes lashed out viciously at an audience that simply believed in him.There’s no way, in looking back on Lennon’s life, not to think of what might have been. Were he now alive, at age 65, would he still be making music and touring, like his quondam band mate McCartney? Or would he have retired by now, to live out the life of an icon so well known for what he did early in life, and so mysterious for what he did not do ever after? It’s impossible to know. All that we’re left with are the memories, and the music, and the poetry of trust and hope with which he imbued his songs.

What John Lennon did, above all else, was look after himself. He wanted love and validation, and he wanted those things on his own terms--the only terms he cared about, and after he had become so legendary, the only ones he needed to accept. Fortunately for us all--fortunately for history--Lennon’s terms involved high standards. He was prideful enough that he wanted to improve his art, both in and past the Beatles, and he succeeded in that ambition. He was also self-important enough to believe that he could wrestle with the times he lived in and make a difference--and the difference he made was immense. Lennon was looking after himself when he made art and proclaimed hopes that would outlast his being. He was looking after himself when he made a family and nurtured and preserved it as his most meaningful legacy--when he looked into his son Sean’s face, and wanted to be worthy of the veneration he saw in that face. He did it when, after all his fuck-ups and all his years of silence, he believed enough in the purpose of what he had to say that he was willing to start over.

Maybe it’s surprising or simply incidental that all this self-interest affected us in such wondrous and valuable ways. Or maybe it isn’t incidental at all. The marvel of John Lennon’s story is that all he really wanted was peace for his own interests--he hated feeling hurt, and he felt it his whole life--and in pursuing that end, he changed the times around him and the possibilities of the times that followed him. Deep-running hurt drove him. It’s what made his story.

There’s another recollection jiggling about in my head. I don’t remember whether it was the night of Lennon’s death, or more likely, the night after, but I do recall gathering together with other music fans in the streets and squares of Portland, where I was living still in 1980. We carried candles and flowers. We wept for the loss of Lennon, just as we had wept over the years for the tragic passings of John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. And then, in a moment that seemed to have no beginning, we began to sing. We sang “Imagine,” which seemed so much the obvious anthem of a world wounded by Lennon’s loss. It was an episode that, for once--for me--didn’t happen on television. However, the separation of fact from fiction was equally daunting.

Imagine that.

READ MORE: “Imagine All the People,” by Dana Cook (Salon); “John Lennon Remembered” (Boston Phoenix); “Fans Can Reimagine a Working Class Hero,” by Steve Knopper (Newsday); “An Unhappy 25th Anniversary,” by Joal Ryan (E! Online); “Fans Mark Anniversary of Lennon’s Murder,” by Pat Milton (AP); “Lennon and Beyond,” by William Bogan (Hughes for America); “Remembering John Lennon” (MSNBC); “John Lennon, Handguns and Me: A 25th Anniversary,” by David Corn; “The Death of John Lennon,” by Elizabeth D. Hoover (American Heritage); “Lennon’s Solo Work Goes Online” (CNN); “The Hero Who Never Looked Down,” by Gary Kamiya (Salon); “The Lost John Lennon Interview,” by Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn (CounterPunch).

1 comment:

greetings to limbo,

yes...I sometimes wonder what John Lennon would be doing these days...I am sure he would be doing something of substance, being a voice for those who can't be heard...he took such great risks for love, peace, family...I don't think that it's going a bit to far to think of him as a prophet for our times (not quite Gandhi) but he was the real deal, he was what he wrote about..."All you need is love"

Post a Comment