[[H I S T O R Y]] * As families of the 12 men who died this week after an explosion at West Virginia’s Sago coal mine come to grips with the emotional ups and downs of that tragedy, it’s worth looking back at the impacts and coverage of previous such mining disasters. For instance, author Bob Greene, writing in today’s New York Times, recalls the media frenzy that surrounded the 1925 entrapment of Floyd Collins, an explorer and guide who perished in a Kentucky cave--but not before William “Skeets” Miller of the Louisville Courier-Journal crawled down into that cavern to interview him (an escapade that would win Miller a Pulitzer Prize in 1926).

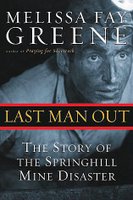

[[H I S T O R Y]] * As families of the 12 men who died this week after an explosion at West Virginia’s Sago coal mine come to grips with the emotional ups and downs of that tragedy, it’s worth looking back at the impacts and coverage of previous such mining disasters. For instance, author Bob Greene, writing in today’s New York Times, recalls the media frenzy that surrounded the 1925 entrapment of Floyd Collins, an explorer and guide who perished in a Kentucky cave--but not before William “Skeets” Miller of the Louisville Courier-Journal crawled down into that cavern to interview him (an escapade that would win Miller a Pulitzer Prize in 1926).Another case, more comparable to the Sago mine incident, occurred in Canada in 1958 and provided the basis for Melissa Fay Greene’s powerfully detailed 2003 history, Last Man Out: The Story of the Springhill Mine Disaster.

Nationally televised disaster coverage is so common nowadays, it’s easy to forget the very first such focus: the October 1958 collapse of North America’s deepest coal mine, in Springhill, Nova Scotia. As Greene recalls in Last Man Out, media attention made that ordeal alternately heart-rending and heart-warming. Of the 174 men who were working the three-level excavation when shifting rock suddenly destroyed it, 99 escaped alive. But 19 of those surviving miners were trapped underground for more than a week, in a lightless purgatory without food or water or any way to let the outside world know they still awaited salvation. Drawing on extensive interviews with many of this tragedy’s principals, Greene (probably best known for her 1991 book, Praying for Sheetrock) winds together parallel story threads. She follows the heroic miners--trapped in two separate parties, divided by 400 feet of solid rock--as they minutely divide candy bars and communal urine supplies, trying to maintain both health and hope. She also keeps track of their families, who watch aluminum caskets emerge from the mine entrance with demoralizing regularity. “It seemed like a malevolent factory operating in reverse: hoisting the dead in their coffins out of their burial, one by one,” Greene writes.

There are sections of Last Man Out that creak with the copiousness of Greene’s research. However, her story benefits by an eccentric cast of characters--especially Maurice Ruddick, a comradely black family man whom the media dubbed “the Singing Miner,” and Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin, the rabble-rousing racist who (along with TV host Ed Sullivan) would turn the rescued miners into minor celebs. As harrowing as their underground entrapment was, those men found themselves equally “lost” in their release. Renown is fleeting, Greene makes clear, but being forgotten sticks with you forever.

No comments:

Post a Comment