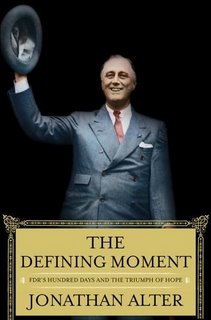

[[A D V I C E]] * Everybody, it seems, wants to tell George W. Bush how to revive his moribund, scandalized, and unpopular presidency. Now, he’s even receiving advice from the grave. Well, in a sense, anyway. Jonathan Alter, the eminently readable Newsweek columnist and political analyst whose new book, The Defining Moment: FDR’s Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope, has just been published, this week compares how President Franklin D. Roosevelt dealt with the crises he faced during the 1930s and ’40s (the Great Depression, World War II, his own polio) to what Bush has done--and hasn’t done--in the years since the September, 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

[[A D V I C E]] * Everybody, it seems, wants to tell George W. Bush how to revive his moribund, scandalized, and unpopular presidency. Now, he’s even receiving advice from the grave. Well, in a sense, anyway. Jonathan Alter, the eminently readable Newsweek columnist and political analyst whose new book, The Defining Moment: FDR’s Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope, has just been published, this week compares how President Franklin D. Roosevelt dealt with the crises he faced during the 1930s and ’40s (the Great Depression, World War II, his own polio) to what Bush has done--and hasn’t done--in the years since the September, 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.Both politicians, Alter writes, were raised amidst wealth, “had a clubby charm and enjoyed bestowing cutting nicknames on aides. Both were tagged by top pundits of the day with the exact same epithet--‘lightweight.’ Both lost for higher office, suffered business setbacks and experienced a personal crisis before becoming governor of a major state. But the crises left entirely different imprints on the political style and character of their presidencies.” In Democrat Roosevelt’s case, he became a stronger, less snobbish, more empathetic man after being stricken with polio at age 39. He went on to “[restore] the hope of polio patients, though neither he nor they would ever walk again.” Then,

Two weeks after barely dodging assassination in Miami in February of 1933, Roosevelt took office and performed a similar conjuring act on a larger stage. With the banks closed and millions of Americans wiped out, FDR used his “first-class temperament” to treat the mental depression of Americans without curing their economic one. In the days following his “fear itself” Inaugural and first “Fireside Chat,” the same citizens who had lined up the month before to withdraw their last savings from the bank (and stuff it under the mattress or tape it to their chests) lined up to redeposit patriotically. This astounding act of ebullient leadership marked the “defining moment” of modern American politics, when Roosevelt saved both capitalism and democracy within a few weeks and redefined the bargain--the “Deal”--the country struck with its own people.Part of Roosevelt’s success in the Oval Office can be attributed to his flexibility. “[C]alling for ‘bold, persistent experimentation,’ he turned flexibility into a principle. When man met moment in 1933, FDR cut left and right at once, putting people to work and regulating Wall Street for the first time, but also resisting pressure to nationalize the banks and slashing federal spending by 30 percent, the deepest cuts ever.” By contrast, Alter explains, Republican Bush emerged from his own “debilitating disease” (“a battle with the bottle that left his wife Laura saying, ‘It’s me or Jack Daniels”) with “a single-minded focus and discipline that took him far. But when discipline hardens into dogma, a president loses the suppleness to respond to problems. Bush’s adherence to routine--a frequent attribute of those who have beaten substance abuse problems--may have slowed his adjustment to new circumstances.” (Which may account for why, after 9/11, he fell back on his already-conceived plan to launch a “pre-emptive” war against Saddam Hussein, even though the “war on terror” should have led the prez in other directions.)

Like Bush, the columnist states, “FDR took an expansive view of presidential power.

But he didn’t circumvent Congress, as Bush did on warrantless wire-tapping. On March 5, 1933, his first full day in office, Roosevelt toyed with giving a speech to the American Legion in which he essentially created a Mussolini-style private army to guard banks against violence. One draft had Roosevelt telling middle-age veterans, long since returned to private life, that “I reserve to myself the right to command you in any phase of the situation that now confronts us.”Several other of Alter’s comparisons between these two polarizing chief executives catch my eye. He observes that “After 9/11, Bush had a moment of Roosevelt-style crisis oratory. But FDR used his speeches to calm fears and unify the nation; Bush has sometimes used his to stoke fears and score political points.” And he writes: “[W]here Bush has often seen the war on terror as a chance for partisan advantage, FDR viewed World War II as a time to reach across party lines. He appointed Herbert Hoover’s secretary of state, Henry Stimson, his secretary of war, and the 1936 GOP candidate for vice president, Frank Knox, his navy secretary. He even brought his 1940 Republican opponent, Wendell Willkie, into the fold.” Particularly interesting are the great differences between Bush and Roosevelt on the issue of public accountability: “Bush is not much of a believer in [it],” Alter notes. But “FDR knew it could make him a more effective president. He held two press conferences a week and instead of shunning Congress’s oversight of Halliburton-style profiteering during the war, he put the main critic, Sen. Harry Truman, on the 1944 ticket.”

When I saw this document in the Roosevelt Library, my eyes nearly popped out. This was dictator talk--a power grab. But FDR didn’t give that speech. Although establishment figures like the columnist Walter Lippmann urged Roosevelt to become a dictator (Mussolini was highly popular in the U.S. and the word, amazingly enough, had a positive connotation at the time), the new president decided to run everything past Congress--even the arrogant and ill-fated effort to “pack” the Supreme Court in 1937.

That sort of willingness to embrace contrary opinions and to be strengthened by them--a hallmark, too, of Abraham Lincoln’s “team of rivals” presidency--showed a core of courage and confidence in Roosevelt, which the more coddled and self-protective Bush is noticeably lacking. And because FDR was made of sterner, more pliable, and less ideological stuff, any posthumous lessons he might have to impart would likely be lost on his most recent successor. Maybe the next guy--or woman--will be better prepared to take Roosevelt’s example to heart.

READ MORE: “‘Lightweight’ FDR Should Give Democrats Hope,” by Jonathan Alter (The Huffington Post).

No comments:

Post a Comment