Born in Henderson, New York, in 1846, but reared in Chicago, Burnham became one of the foremost American architects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and possessed an expertise in urban planning that, for his time, was unrivaled in the United States. A number of the elegant edifices he created with his business partner, John Wellborn Root, are now beloved landmarks in the Windy City--from the broad-shouldered Rookery Building (1885-88) to the towering Reliance Building (1890-95), “a direct ancestor of today's glass-and-steel skyscrapers.” But after Root died in 1891, the ambitious Burnham further broadened his artistic parameters. He chaired the 1901 commission supervising modifications to Pierre L’Enfant’s original plan for Washington, D.C, and designed the U.S. capital’s exquisite Union Station (1907). He went on to create Cleveland’s civic center, and in 1909 drew up the comprehensive plan for Chicago’s expansion, hoping to turn his adopted town into a “Paris on the Prairie.” Burnham was subsequently commissioned to formulate a similarly forward-thinking design strategy for San Francisco, California, teeming with new diagonal streets, elegant boulevards, an abundantly landscaped government center and cultural district, and parks everywhere. He submitted this blueprint for half a century’s urban enhancement in September 1905. Unfortunately, that was just seven months before San Francisco’s great earthquake and fire, which left most of its downtown a smoking ruin and convinced impatient local burghers to abandon Burnham’s architectural idealism in favor of rebuilding along the same lines the city had previously followed.

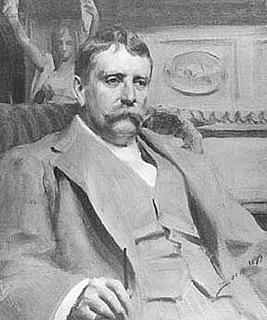

Born in Henderson, New York, in 1846, but reared in Chicago, Burnham became one of the foremost American architects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and possessed an expertise in urban planning that, for his time, was unrivaled in the United States. A number of the elegant edifices he created with his business partner, John Wellborn Root, are now beloved landmarks in the Windy City--from the broad-shouldered Rookery Building (1885-88) to the towering Reliance Building (1890-95), “a direct ancestor of today's glass-and-steel skyscrapers.” But after Root died in 1891, the ambitious Burnham further broadened his artistic parameters. He chaired the 1901 commission supervising modifications to Pierre L’Enfant’s original plan for Washington, D.C, and designed the U.S. capital’s exquisite Union Station (1907). He went on to create Cleveland’s civic center, and in 1909 drew up the comprehensive plan for Chicago’s expansion, hoping to turn his adopted town into a “Paris on the Prairie.” Burnham was subsequently commissioned to formulate a similarly forward-thinking design strategy for San Francisco, California, teeming with new diagonal streets, elegant boulevards, an abundantly landscaped government center and cultural district, and parks everywhere. He submitted this blueprint for half a century’s urban enhancement in September 1905. Unfortunately, that was just seven months before San Francisco’s great earthquake and fire, which left most of its downtown a smoking ruin and convinced impatient local burghers to abandon Burnham’s architectural idealism in favor of rebuilding along the same lines the city had previously followed.Not all of his contemporaries were pleased with Burnham’s contributions to their art. Some positively bristled at the Columbian Exposition’s obeisance to a traditional European architectural idiom over a less-adorned American one. The great Chicago building designer Louis Sullivan contended that the world’s fair had “set back architecture fifty years.” However, many fairgoers in 1893, as well as scores of visiting mayors, town councilmen, and even President Grover Cleveland, hoped that Burnham’s ordered, well-scrubbed, and festive model for cities of the future would eventually drive out the cluttered ugliness of their own industrialized hometowns. And Frank Lloyd Wright later applauded Burnham for his “masterful use of the methods and men of his time” and for being “an enthusiastic promoter of great construction enterprises.”

Although Burnham’s structures are now considerably better known than he is, he did gain a recent burst of posthumous renown as one of the two principal leads in Erik Larson’s 2003 nonfiction best-seller, The Devil in the White City.

No comments:

Post a Comment