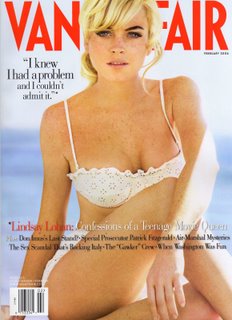

[[C R I M E]] * Most of the publicity attending the February 2006 issue of Vanity Fair centers on that mag’s interview with its splendidly freckled, 19-year-old cover girl, actress-pop star Lindsay Lohan, whose confessions about bulimia and “a little” drug use made headlines around the globe (only to spur denials from the interviewee herself). But more interesting, really, is VF’s profile of Patrick Fitzgerald, the Chicago-based special prosecutor investigating the Republican White House’s CIA leak scandal (aka Plamegate). The same 45-year-old U.S. attorney who, in late October, brought a five-count indictment against Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, which led to Libby’s resignation--and who is said to be still pursuing charges against George W. Bush’s deputy chief of staff, Karl Rove. A few choice selections from David Margolick’s look at this scourage of al Qaeda turned lefty hero:

[[C R I M E]] * Most of the publicity attending the February 2006 issue of Vanity Fair centers on that mag’s interview with its splendidly freckled, 19-year-old cover girl, actress-pop star Lindsay Lohan, whose confessions about bulimia and “a little” drug use made headlines around the globe (only to spur denials from the interviewee herself). But more interesting, really, is VF’s profile of Patrick Fitzgerald, the Chicago-based special prosecutor investigating the Republican White House’s CIA leak scandal (aka Plamegate). The same 45-year-old U.S. attorney who, in late October, brought a five-count indictment against Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, which led to Libby’s resignation--and who is said to be still pursuing charges against George W. Bush’s deputy chief of staff, Karl Rove. A few choice selections from David Margolick’s look at this scourage of al Qaeda turned lefty hero:● “In ‘Fitzie’’s world, stories abound about the famous eccentricities of this lifelong bachelor and inveterate workaholic. There are the tales of the socks and underwear he keeps in his office desk, of having to stop at his office en route to weddings to pick up a suit, of colleagues calling at three in the morning to leave messages on his office phone and hearing him pick up. From his discombobulated apartments comes lore about lasagna grown petrified after three months in his oven--that is, once he’d had his stove connected. (For months or years on end, depending on the account, it was not, and he kept newspapers stacked atop it.) There are his practical jokes: drafting a fake (and adverse) judicial decision for a colleague on tenterhooks awaiting the real one, or convincing another colleague that one could tell the Chinese dialect people spoke by taking prints of their tongues. There are also accounts of his occasional, high-testosterone vacations: hang-gliding and bungee-jumping, though he is afraid of heights; scuba-diving, though he can’t really swim.”

● “Fitzgerald showed an instant aptitude for trial work; he was not one of those anal-retentive types who had to write everything out beforehand. And as disheveled as his files and personal life sometimes seemed, his brain was a marvel of organization. In 1993 he handled his first big case, of Mob bigwigs John and Joseph Gambino, associates of John Gotti’s, charged with murder, racketeering, and narcotics trafficking. After a four-month trial--during which Mob turncoat Salvatore ‘Sammy the Bull’ Gravano testified--a lone holdout hung the jury. So devastating was the outcome that Fitzgerald went into a deep funk and considered changing careers. (To avoid a re-trial, the two mobsters eventually pleaded guilty to lesser charges.)

“By this point, Fitzgerald’s mother had died and his father had Alzheimer’s disease; still, when then attorney general Janet Reno gave Fitzgerald an award for his work on the Gambino case, he brought his father, then only intermittently lucid, with him to Washington and posed with him by the bust of one of the elder Fitzgerald’s heroes, Robert Kennedy, in the Justice Department’s courtyard. It was a moment that few there could forget.”

● “Supporters and detractors alike agree that in Fitzgerald’s Manichaean universe nothing is more heinous than lying, especially when the lie comes from a lawyer. “Pat doesn’t take the actions of a criminal personally,” says [fellow attorney] David Kelley. “A criminal is expected to do that. A lawyer is not expected to lie.” Perhaps, some speculate, this explains the fate of Scooter Libby, Columbia Law School ’75, who claimed--falsely, Fitzgerald insists--that he had heard about [Valerie] Plame’s CIA ties only from reporters, and that he didn’t even know if it was true. … Fitzgerald, his critics speculate, may be above partisan politics, but he is not beyond personal pique. ‘He was not happy with Mr. Libby, and obviously he took it personally,’ says Joseph diGenova, a former U.S. Attorney.”

● “What’s next for Fitzgerald after Plame and Chicago is anyone’s guess. In a sense, he is checkmated; no other job would give him the rush he now enjoys. All of the cushy perches to which lawyers of his ilk usually parachute--the fancy law firms and large corporations--hold little appeal for him. He hasn’t the stomach for elective office, and a high-level political appointment--to head the FBI or CIA, or to become attorney general--would require a politician bold, or desperate, enough to tolerate someone clearly beyond his control.”

Jane Hamsher, over at the FireDogLake blog, covers Margolick’s Fitzgerald profile in more copious detail here and here.

No comments:

Post a Comment