“orator who saved the nation”--with a likeness of Ronald Reagan. The sponsor of this legislation, Republican state Senator Dennis Hollingsworth, told The New York Times that he had been surprised, during a visit last year to Washington, D.C., to discover that California’s sole contributions to Statuary Hall were representations of 18th-century missionary Junípero Serra and King. “To be honest with you, I wasn’t sure who Thomas Starr King was,” he said to the Times. “And I think there’s probably a lot of Californians like me.” He complained further, that King wasn’t a native Californian (which, of course, was true of Reagan as well: he was born in Illinois.) There was some opposition to King’s replacement in the Capitol, including from David Sammons, the head of Berkeley’s Starr King seminary, who was quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle as saying: “In California, the two people who were chosen [for inclusion in the hall] were both clergy. Starr King is a stellar example of religion having a positive effect on the world.” However, the Democrat-dominated legislature easily passed Hollingsworth’s bill. It’s a sad day when the ignorance of a GOP lawmaker results in the expulsion from D.C.’s most famous statuary showcase a tribute in bronze to an individual who not only helped hold the United States together during the Civil War, but was instrumental in saving what’s now Yosemite National Park. That he should be replaced by Reagan, whose two terms in the White House served to divide the nation, and whose environmental record was anything but stellar (“Trees,” Reagan once said, “cause more pollution than automobiles do”), is nothing short of insulting. Even if Dennis Hollingsworth doesn’t know the history of Thomas Starr King, that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t. Below, I am featuring a chapter from my 1995 book, San Francisco, You’re History!, in which I recount King’s many contributions to his state and era.]

“orator who saved the nation”--with a likeness of Ronald Reagan. The sponsor of this legislation, Republican state Senator Dennis Hollingsworth, told The New York Times that he had been surprised, during a visit last year to Washington, D.C., to discover that California’s sole contributions to Statuary Hall were representations of 18th-century missionary Junípero Serra and King. “To be honest with you, I wasn’t sure who Thomas Starr King was,” he said to the Times. “And I think there’s probably a lot of Californians like me.” He complained further, that King wasn’t a native Californian (which, of course, was true of Reagan as well: he was born in Illinois.) There was some opposition to King’s replacement in the Capitol, including from David Sammons, the head of Berkeley’s Starr King seminary, who was quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle as saying: “In California, the two people who were chosen [for inclusion in the hall] were both clergy. Starr King is a stellar example of religion having a positive effect on the world.” However, the Democrat-dominated legislature easily passed Hollingsworth’s bill. It’s a sad day when the ignorance of a GOP lawmaker results in the expulsion from D.C.’s most famous statuary showcase a tribute in bronze to an individual who not only helped hold the United States together during the Civil War, but was instrumental in saving what’s now Yosemite National Park. That he should be replaced by Reagan, whose two terms in the White House served to divide the nation, and whose environmental record was anything but stellar (“Trees,” Reagan once said, “cause more pollution than automobiles do”), is nothing short of insulting. Even if Dennis Hollingsworth doesn’t know the history of Thomas Starr King, that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t. Below, I am featuring a chapter from my 1995 book, San Francisco, You’re History!, in which I recount King’s many contributions to his state and era.]* * *

No student of American history can fail to be moved by the cool bronze and marble figures that encircle Statuary Hall, the vast former House of Representatives chamber at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Most of the 92 figures honored there are immediately familiar, from Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee to Senator Henry Clay, Mormon leader Brigham Young, and President John Quincy Adams. But every once in a while the echo of your footfalls will stop abruptly, and you'll find yourself standing quizzically before the representation of a person whose notoriety has somehow been displaced by successive waves of the more recently famous.Who, for instance, was Thomas Starr King?

In mid-19th century California, that question would have been as unlikely as someone today asking Who is Bill Clinton? or Who is Sean Connery? or Who is Janet Jackson? After all, had it not been for “Starr King,” as he was best known, this state might have thrown its lot in with the Confederacy during the Civil War and might later have lost Yosemite to private exploiters.

It’s surprising how much influence King had in San Francisco and California, given how little of his life was actually spent here. He was born in New York in 1824, and after his family moved to New England, educated himself in history, languages, classical literature, and theology. Following stints as a grammar school teacher and a bookkeeper, he heeded the same call to religious toil that had sounded for his father, a Universalist minister. By 1848 he was pastor at Boston’s Hollis Street Unitarian Church.

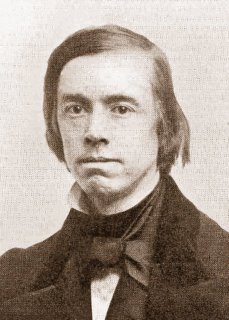

King was a slight man with a weak chin and thin, straight blond hair, and in photos he has the sort of tightly controlled features and intense eyes that are common on old-time undertakers. But his voice ... His voice was the kind to silence a fidgety crowd, to quiet even an unruly mob. Its strong, confident timbre was near-powerful enough to imbed itself in church walls. People would come faithfully before his rostrum on Sundays to not only hear what he said, but to enjoy his electric delivery. As his friend, the anti-slavery advocate and Unitarian minister Theodore Parker phrased it, King had “the grace of God in his heart and the gift of tongues.” It wasn’t long before he ranked among Boston’s most popular preachers.

However, King was omnivorous in his interests. In 1860 he published a lovingly detailed appreciation of New Hampshire called The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscapes, and Poetry. He also joined the Lyceum circuit, rivaling Henry Ward Beecher as a lecturer on various topics of the times.

Like many other well-read people in pre-Civil War America, King was concerned that trouble would arise from the 1860 presidential race--an election that would help decide whether the United States should remain whole or be cleaved asunder by the poised ax of slavery. The Democratic Party’s hesitation to nominate Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, “the only Democrat who could have reached out beyond the slaveholding South and gathered up enough votes from the border states to win,” according to American Heritage magazine, and the subsequent formation of a Democratic splinter group called the Constitutional Union party, almost assured lawyer Abraham Lincoln’s election on behalf of the new Republican Party. If that happened, King knew, the South was likely to choose secession over governance by a president who, despite some wishy-washiness on the issue, had been firmly cast in the public’s mind as an abolitionist.

Unwilling to sit out the coming conflict in the socially stratified seclusion of Beantown, King took up an invitation in 1860 to lead a struggling flock of Unitarians in faraway and still small (population 56,800) San Francisco. Accompanied by his wife, Julia, he booked ship passage to the Bay Area via Panama, explaining to a friend that “I do think we are unfaithful in huddling so closely around the cozy stove of civilization in this blessed Boston, and I, for one, am ready to go into the cold, and see if I am good for anything.”

* * *

At the time, California was busily charting its political course. Historians disagree, but something between 7 percent and 40 percent of the state’s 380,000 inhabitants had come from slaveholding areas. Only seven of California’s 53 newspapers endorsed Lincoln for the presidency, and after the election was decided in the old rail-splitter’s favor, more than a few of those papers that had opposed him called on the state to splinter from the Union and hook up with Oregon as an independent Republic of the Pacific. Back in what was then called Washington City, California Representative John C. Burch called on this state to “raise aloft” the Bear Flag that had flown above the short-lived California Republic in 1846.After the Confederate siege of Charleston, South Carolina’s Fort Sumter in April 1861, “anti-Union plots and rumors of plots proliferated” in both Oregon and California, Alvin M. Josephy Jr. writes in The Civil War in the American West. “Pro-Southern organizations, including the conspiratorial Knights of the Golden Circle, spread through the two states, the Bear Flag, as well as palmetto flags honoring South Carolina, flew in a number of California towns, and Unionists’ fears of a secessionist coup mounted.”

There had also been fears concerning the loyalty of federal forces on the West Coast, headed as they were by Brigadier General Albert Sidney Johnston, a Texan with Southern sympathies who had been appointed during the last days of James Buchanan’s presidency to supervise Union armies in not only California, but also Oregon and Washington Territory. But Johnston acted unwaveringly in his command, calling in additional troops to fortify San Francisco’s unfinished Fort Point and transferring ammunition from the federal arsenal at Benicia to the better-protected fortress on Alcatraz Island. (Only after the Lincoln administration grew suspicious of Johnston and replaced him with Brigadier General Edwin V. “Bull Head” Sumner, just prior to the Fort Sumter engagement, did Johnston journey secretly across Southern California to offer his services to the Confederacy in Texas.)

Starr King had little patience with secessionists. His voice rang out from San Francisco: “Our city turns her face persistently towards the East--signifying that California has no insane vision of independence; that she desires no isolated sway over the Pacific, but is bound by loyalty to the empire whose flag she plants on Mendocino, the Hatteras of the West.” King’s physical health “was not good,” explained B.E. Lloyd in Lights and Shades in San Francisco. “An affection of the throat frequently gave him trouble.” Yet he traveled the state, from cities to dreary mining camps, employing biblical themes and his powerful oratorical presence on behalf of Lincoln and California’s essential obeisance to the Union. In one of King’s most oft-quoted speeches, he demanded that “the doctrine of secession be stabbed with two hundred thousand bayonet wounds, and trampled to rise no more.”

* * *

Such patriotic fervor weighed mightily on legislators as they met in Sacramento, and much to the surprise of California’s all-Democratic and anti-Lincoln delegation in the nation’s capital, on May 17, 1861, a joint-house resolution was released, declaring that the 31st state would remain firmly in the Union fold. Confirming California’s position were the state elections of that same year, which listed in favor of Republicans and Unionist Democrats, and resulted in sending railroader Leland Stanford to Sacramento for two years as the state’s first Republican governor.Even after California had abjured from becoming a Confederate hot spot, King didn’t lose interest in the War Between the States. In fact, with his impassioned endorsements of the United States Sanitary Commission, the “Red Cross of the Civil War,” California managed to raise $1,234,000 to help care for sick and dying soldiers--about one-quarter of what the relief agency received from all over the country during the four years of bloody hostilities. Dr. Henry Whitney Bellows, New York founder of the Sanitary Commission, described King as “the eloquent voice, the quickening soul” of his organization’s California contingent.

But the clergyman’s energies weren’t exhausted completely into the political arena. He sought to enhance San Francisco’s literary reputation, making friends with writers such as Bret Harte and, through him, becoming acquainted with such recipients of later fame as Mark Twain and the stripling poet Charles Warren Stoddard.

He took the opportunity as well to appreciate California’s natural bounty. An early environmentalist, King had a poet’s talent to describe the state’s mountains, rivers, and deserts to San Francisco audiences who had seen very little of their huge, still-unfettered homeland. As he had earlier sat down to honor New Hampshire in print with The White Hills, so he planned to champion the Bear State’s more rugged landscape, with special emphasis given to the waterfalls, forests, and cliff faces of the Yosemite Valley. “Great is granite,” King proclaimed, sharing a passion he’d gained from years of mountain climbing, “and Yosemite is its prophet.”

It was partly through King’s efforts that Yosemite--which he had visited for the first time shortly after his arrival in California, in 1860--survived to be written about in 1912 by Scottish philosopher and scientist John Muir. During the decade following Yosemite’s “discovery” in 1851, the U.S. Cavalry had herded the Ahwahneechee Indians away from their sacred valley, and it was rapidly being fenced, farmed, and otherwise homesteaded. Travelers who visited the area, hoping to enjoy wilderness delights that they had read about in newspaper descriptions, were disappointed to see alpine valleys given over to the pleasure of cud-sucking cattle.

Powerful easterners who read King’s dispatches about Yosemite’s slow destruction were finally moved to action. In 1864, Frederick Law Olmsted, superintendent of New York’s Central Park and the country’s most respected landscape architect, encouraged President Lincoln and Congress to preserve Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees as a natural scenic area safe from construction. This was the nation’s first such experiment in environmental protection, and it set the stage for many more preservation actions in the future.

But Starr King didn’t ignore his primary responsibility to religion. Indeed, on January 10, 1864, just two months before his career came to an unexpectedly early close, he dedicated the First

Unitarian Church of San Francisco, a stirring $90,000 Gothic edifice, with seating for 1,500 God-fearing souls, that still stands at Franklin and Geary streets, in Japantown.

Unitarian Church of San Francisco, a stirring $90,000 Gothic edifice, with seating for 1,500 God-fearing souls, that still stands at Franklin and Geary streets, in Japantown.* * *

Cause of King’s death on March 4, 1864, when he was just 39 years old, was ascribed to the one-two punch of diphtheria and pneumonia. The San Francisco Bulletin made room for Bret Harte’s final poetic panegyric to the city’s most outspoken humanitarian. The Alta California newspaper gave over most of its front page to King’s passing, noting sadly that the preacher’s book on Yosemite had never been finished. The United States Mint in San Francisco closed in his memory, along with other government offices, courts, and businesses. In Sacramento, legislators had the pastor’s portrait mounted in the statehouse and they credited him officially as “the man whose matchless oratory saved California for the Union.”King’s death-bed request had been to “Keep my memory green.” But beyond the memories of his loyal followers, little in the way of a lasting tribute was made until 1892, when a statue was raised on the pastor’s behalf in San Francisco. Sculpted by the famed Daniel Chester French (whose work can be found peppered about New York City), it stands in Golden Gate Park, at one corner of the Music Concourse. His portrayal in bronze at Statuary Hall, the creation of Haig Patigian, was unveiled in 1931. The remembrance that might have stirred Thomas Starr King’s heart most, though, is not a thing of artificial beauty, but of natural eminence--a literal way of keeping King’s memory “green.” After Yosemite won national park status in 1890, one of its mountains and a redwood in the Mariposa Grove were named for the man whose eloquence had helped save them.

No comments:

Post a Comment